1. Early Electronic Monitoring in the Late 20th Century

Electronic Monitoring (EM) for non-custodial offenders was first introduced in the early 1980s. By 1987, more than 900 individuals across 21 U.S. states were participating in EM programs. With the spread of personal computers and advances in microchip technology, the number of EM devices in use had grown to over 25,000 by 1998 in major Western countries.

The most common application at that time remained house arrest or home curfew, ensuring that offenders stayed within designated locations. For example, offenders placed under home confinement were required to remain at home during specific curfew hours. This was one of the earliest applications of EM and continues to be one of its primary uses today.

The system consisted of two devices:

- Personal Identification Device (PID): a tag attached to the offender.

- Home Monitoring Unit (HMU): a receiver installed in the offender’s residence.

The PID contained a short-range radio transmitter that broadcast signals at random intervals of 1 to 10 seconds to the HMU. Typically worn on the ankle (rarely on the wrist, except in justified cases), it was waterproof, tamper-resistant, and could not be removed without triggering an alarm. This made it widely known as an ankle monitor (or electronic bracelet).

Installation required special tools to lock the strap around the offender’s ankle while activating tamper-detection sensors. The PID transmitted signals that included its serial number and status (battery level, movement, tamper alerts, etc.). The strap contained a fiber-optic cable to detect cuts or tampering. If broken, the light signal was interrupted, triggering a tamper alert to the monitoring provider. At the same time, the strap was designed to be cut quickly in emergencies (such as accidents or medical treatment). The PID battery typically lasted around 12 months, with low-battery alerts beginning after 10 months to remind providers to replace it.

The HMU was installed in the offender’s home and received signals from the PID, verifying whether the monitored person remained within the approved range. During setup, officers tested signal coverage by having the offender move throughout the permitted areas of the residence. The HMU transmitted this information to a central monitoring system via landline or cellular networks.

The HMU also included a two-way telephone system for communication with the monitoring center. This allowed staff to contact the offender for compliance checks (e.g., curfew violations or “home all day” alerts), while offenders could also use it to contact the monitoring center.

In developed countries, the cost of a radio-frequency PID ankle monitor was estimated at about £71.70 (€100.77), while an HMU cost approximately £400 (€562.15).

2. The Impact of GPS on Electronic Monitoring

On May 1, 2000, U.S. President Bill Clinton announced the removal of selective availability (SA), a policy that had intentionally degraded civilian GPS accuracy. This decision immediately improved positioning precision for civilian use, accelerating the adoption of the Global Positioning System (GPS)—a satellite-based navigation system developed over two decades by the U.S. military at a cost of $30 billion.

With GPS receivers providing higher accuracy, GPS-based EM quickly expanded as a more compact and affordable tool for offender tracking. Today’s devices offer improved adaptability and include features such as voice communication, audio/vibration alerts for schedule violations, enhanced mapping and case management software, and the ability to set movement-restriction zones to protect victims.

The rapid advancement of GPS and mobile communication systems expanded EM applications to broader areas of criminal justice, including:

- Exclusion zones: preventing offenders from entering restricted areas or approaching complainants, victims, or co-offenders.

- Continuous monitoring: enabling authorities to track offenders without restricting daily activities, allowing them to work or support their families while still being supervised.

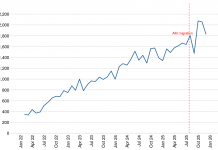

According to a Pew Charitable Trusts survey in December 2015, over 125,000 people in the U.S. were being tracked with GPS ankle monitors on a single day—an increase of nearly 140% from the 53,000 tracked in 2005. The study found that the surge in GPS adoption was the main driver behind the decade-long growth of EM use.